Understanding Key Value Item (KVI) Pricing Strategies: A Comprehensive Guide

How Key Value Items really work, and why willingness to pay matters more

Summarize article with AI

Updated January 2026

Key Value Items, KVIs, show up in almost every retail pricing playbook. The advice usually sounds simple: pick the items customers care about, price them sharply, and earn the margin back elsewhere.

The problem is that most KVI guidance starts too late. It assumes you already know which items actually shape price perception. In practice, many teams default to "top sellers" or "category staples", then call them KVIs. That can work sometimes, but it can also be wrong, and expensive. High volume does not automatically mean high price sensitivity. A product can sell well for reasons that have nothing to do with price. Another product can quietly be the one customers compare, even if it is not your top seller.

This matters more now than it did a few years ago. Price transparency is higher, competitive moves travel faster, and demand can shift quickly due to promotions, cost changes, or market uncertainty. If your KVI list is built mainly on historical sales, you are building on a moving target. It becomes a fragile foundation. You see what happened at the prices you chose, not what would have happened at the prices you did not choose.

This is why it helps to treat KVI as a demand visibility problem, not a pricing tactic problem.

Instead of asking "Which items are our KVIs?" the better question is: which products influence perception because demand reacts meaningfully when their price changes, and at what price points does that reaction start?

In this guide, we will define what a KVI really is, show where classic KVI approaches break down, and outline a more modern way to identify and manage KVIs. We will also zoom in on a case most articles ignore: companies with only 2 to 15 products, where a single mispriced “hero” item can define your entire price image.

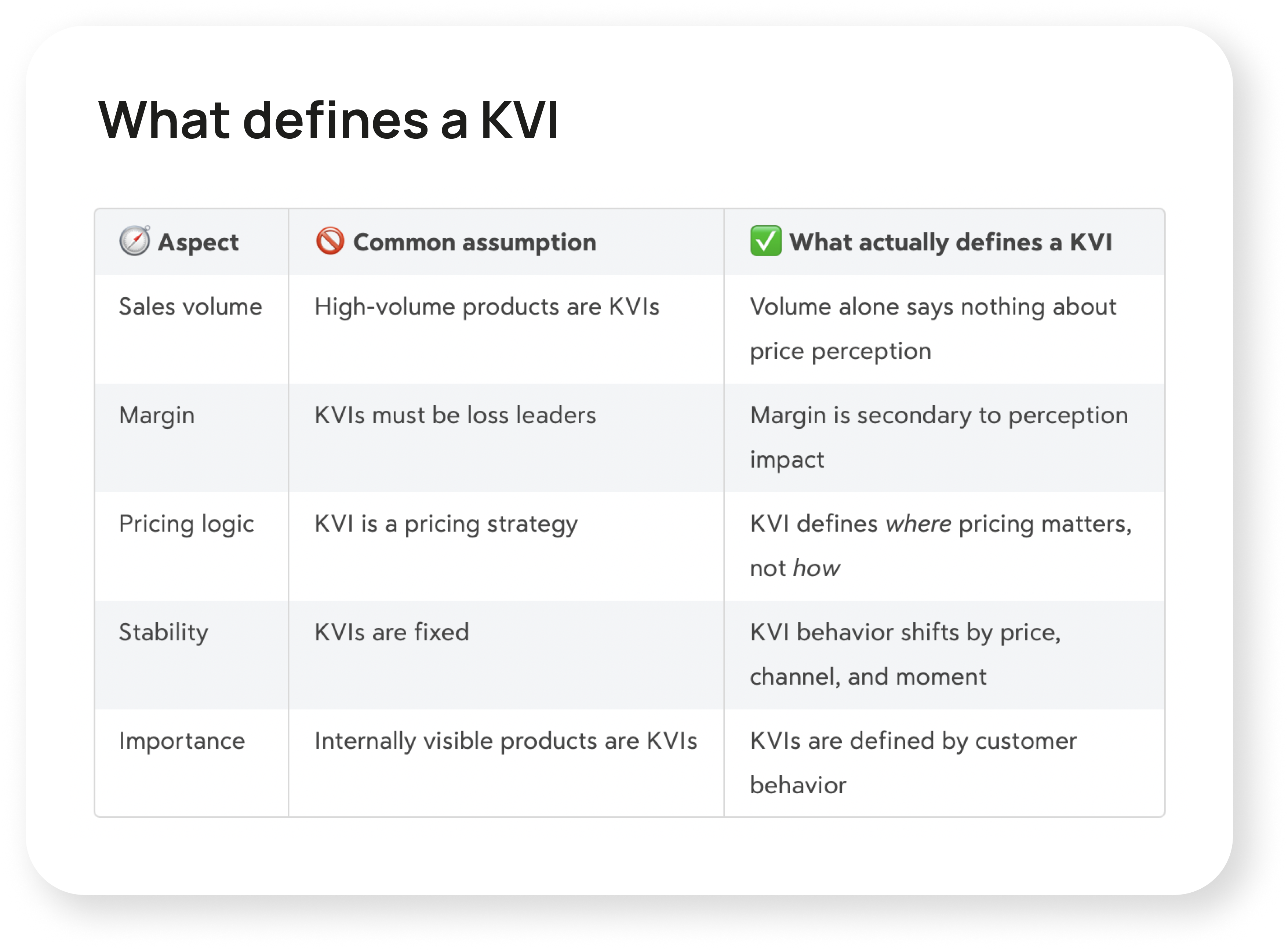

What a KVI really is, and what it is not

Let’s separate what a KVI is from what it often gets confused with.

A Key Value Item is not simply a product that sells a lot.

It is a product that customers notice, remember, and compare, and then use as a shortcut to judge whether a brand or retailer is "expensive" or "good value".

That distinction matters. Many high-volume products are not price anchors at all. They sell because they are habitual, differentiated, or hard to substitute. At the same time, some products with lower total volume can have an outsized impact on perception because customers know roughly what they "should" cost and actively compare them across brands or stores.

This is why KVIs show up so consistently in retail pricing strategies. In grocery, it is often everyday staples like milk, eggs, coffee, or bread. In consumer electronics, it might be a specific TV model, a popular smartphone, or a gaming console. These items act as reference points. When they are priced competitively, customers assume the rest of the assortment is fairly priced. When they are not, trust erodes quickly.

Just as important is what a KVI is not.

A KVI is not automatically a loss leader.

Some KVIs are priced aggressively, others are simply kept in line with the market. The defining feature is not margin, but influence on perception and demand. If lowering the price does not meaningfully change how customers behave or how they perceive your pricing, the item is not acting like a KVI, regardless of how much you discount it.

A KVI is also not a pricing strategy in itself.

Terms like value-based pricing, psychological pricing, or penetration pricing describe how prices are set. KVI describes where pricing attention should be focused. Confusing the two often leads teams to apply generic pricing tactics to the wrong products.

Finally, KVIs are not fixed or universal

The same product can behave like a KVI in one market, channel, or moment, and not in another. A product might be a strong price anchor during a promotion, a launch, or a period of cost pressure, and fade into the background at other times. Treating KVIs as static labels is one of the most common mistakes teams make.

The practical takeaway is simple: a KVI is defined by customer behavior, not by internal labels. It earns its status because changes in its price meaningfully influence demand and perception. Everything else is an assumption that still needs to be tested.

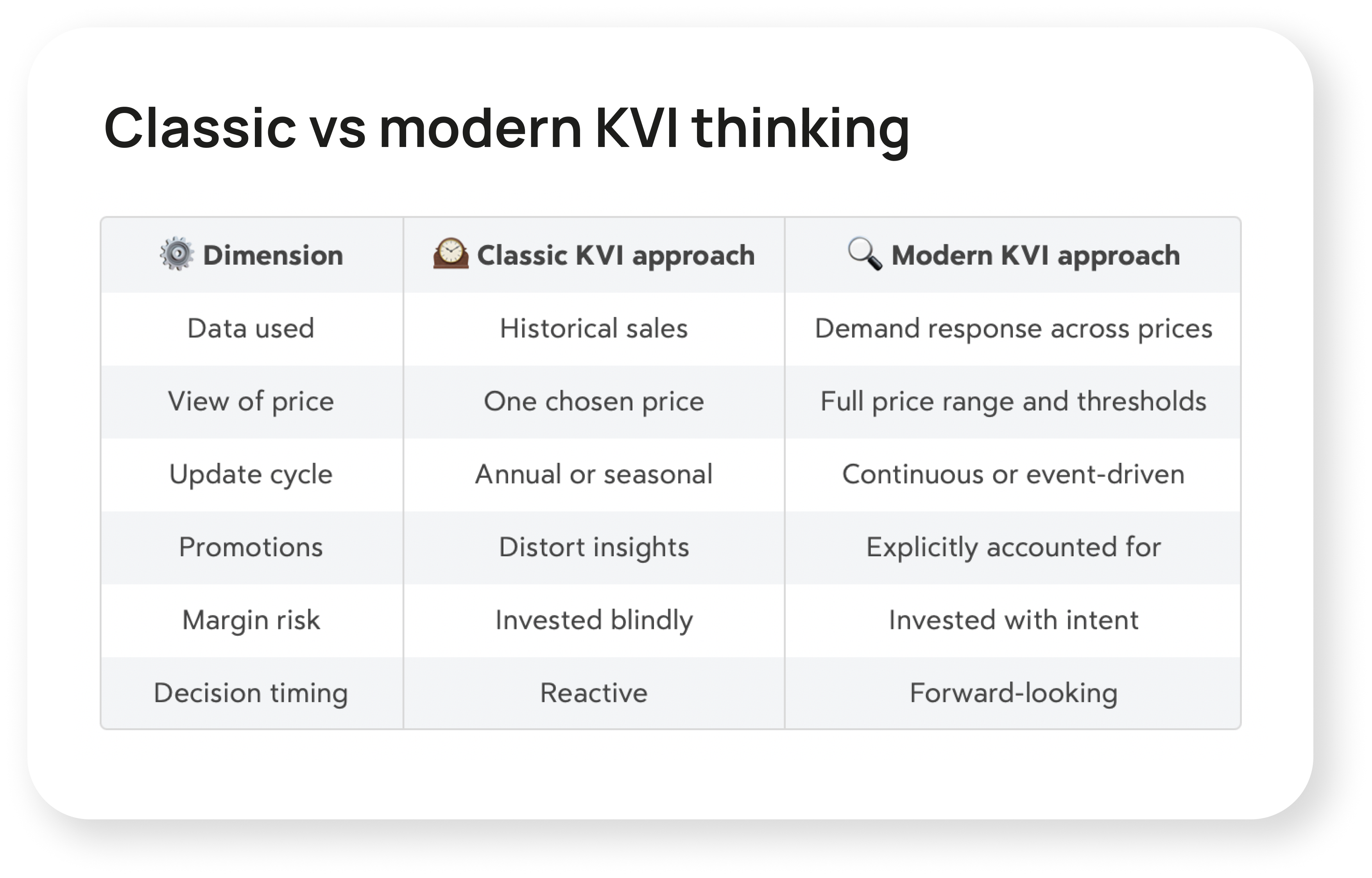

The classic KVI playbook, and why it breaks down today

The idea behind classic KVI pricing is sound. The inputs are the problem.

Most KVI strategies still follow a familiar pattern. Teams look at historical sales, identify the most frequently purchased or highest-volume products, sanity-check them against competitor prices, and declare those items KVIs. Prices are then kept low or matched closely to the market, while margin is recovered on the rest of the assortment.

This approach is understandable. It is simple, operationally manageable, and often grounded in years of category experience. In stable markets, it can even work reasonably well. The problem is that it relies on assumptions that no longer hold.

The classic approach breaks down for three reasons:

- Historical sales only show what happened at one chosen price.

They do not tell you how demand would have behaved at higher or lower prices. - Sales data is heavily distorted by context.

Promotions, seasonality, marketing campaigns, and stock availability all shape historical sales data, especially during market shocks and sudden cost changes. - Markets move faster than KVI lists.

Annual or seasonal reviews cannot keep up with weekly competitive moves and shifts in consumer attention.

Finally, the classic playbook tends to treat KVIs as fixed labels rather than situational roles. An item is either a KVI or it is not. In practice, many products only behave like KVIs at certain price levels or in certain moments, such as during a promotion, a launch, or a period of cost pressure. The traditional model has no good way to capture that nuance.

The result is a fragile strategy.

Teams invest margin in the wrong places, miss opportunities to price more confidently where demand is resilient, and react late to changes in customer behavior. The intent behind classic KVI pricing is sound, but the execution is built on a backward-looking view of the market that struggles under modern conditions.

How leading teams identify KVIs today

KVI identification has shifted from labels to signals.

Teams that take KVI pricing seriously have moved away from single-signal thinking. Instead of asking "Which products sell the most?", they look at a combination of signals that together explain which items actually shape price perception and demand.

Leading teams typically look at:

- Basket role

Products that consistently appear in core shopping missions tend to matter more than occasional add-ons. - Purchase frequency, interpreted carefully

High frequency alone is not enough. What matters is whether customers actively notice and remember the price. - Competitive transparency

Products that are easy to compare across brands or retailers are more likely to influence perception. - Demand sensitivity

Items that show meaningful shifts in demand when price moves are stronger KVI candidates than items that remain stable. - Context

KVI behavior varies by channel, region, season, and situation.

Operationally, this often leads to clearer structure. Teams separate everyday KVIs, which anchor the base price image, from promotional KVIs, which anchor expectations during discounts and campaigns. They test scenarios before making changes, rather than learning only after margin has already been given away.

The common thread is a shift from labels to evidence. Instead of declaring something a KVI because it looks important, leading teams ask whether the data shows that price changes on this product actually influence demand and perception. When that question is answered well, KVI pricing becomes far more precise and far less risky.

How KVI thinking changes when you only have 2 to 15 products

With few products, one price sets the tone.

Most KVI frameworks are written for retailers with thousands of SKUs. That breaks down quickly when you only have a handful of products. In a small portfolio, every price carries more weight, and a single mispriced product can define how customers perceive the entire brand.

When you have 2 to 15 products, you do not have the luxury of hiding mistakes. There is no long tail of non-KVIs to quietly recover margin from. That makes KVI thinking more important, not less, but it needs to be applied differently.

The shift usually happens in three ways:

- From lists to roles

One or two products often act as price anchors and define the brand’s price image. - From fixed labels to price-dependent behavior

A product can behave like a KVI at one price and not at another. - From uniform optimization to deliberate roles

Some products signal value. Others capture margin. Others support attachment or upsell.

This is especially relevant in consumer electronics and CPG brands with few SKUs sold through FMCG. A single electronics model can become the reference point customers compare across retailers, while accessories or premium variants carry the economics. In CPG, one core flavor or format often sets the perceived price level of the brand, while extensions and multipacks do the margin work. Treating all products as equal from a pricing perspective blurs these dynamics and weakens decision-making.

For small portfolios, KVI strategy is less about copying retail playbooks and more about discipline. It is about knowing which product defines your price image, understanding how sensitive demand is at different price levels, and being deliberate about where you invest and where you protect margin. When those roles are clear, pricing decisions become simpler and more consistent, even in volatile markets.

KVI through a demand-first lens

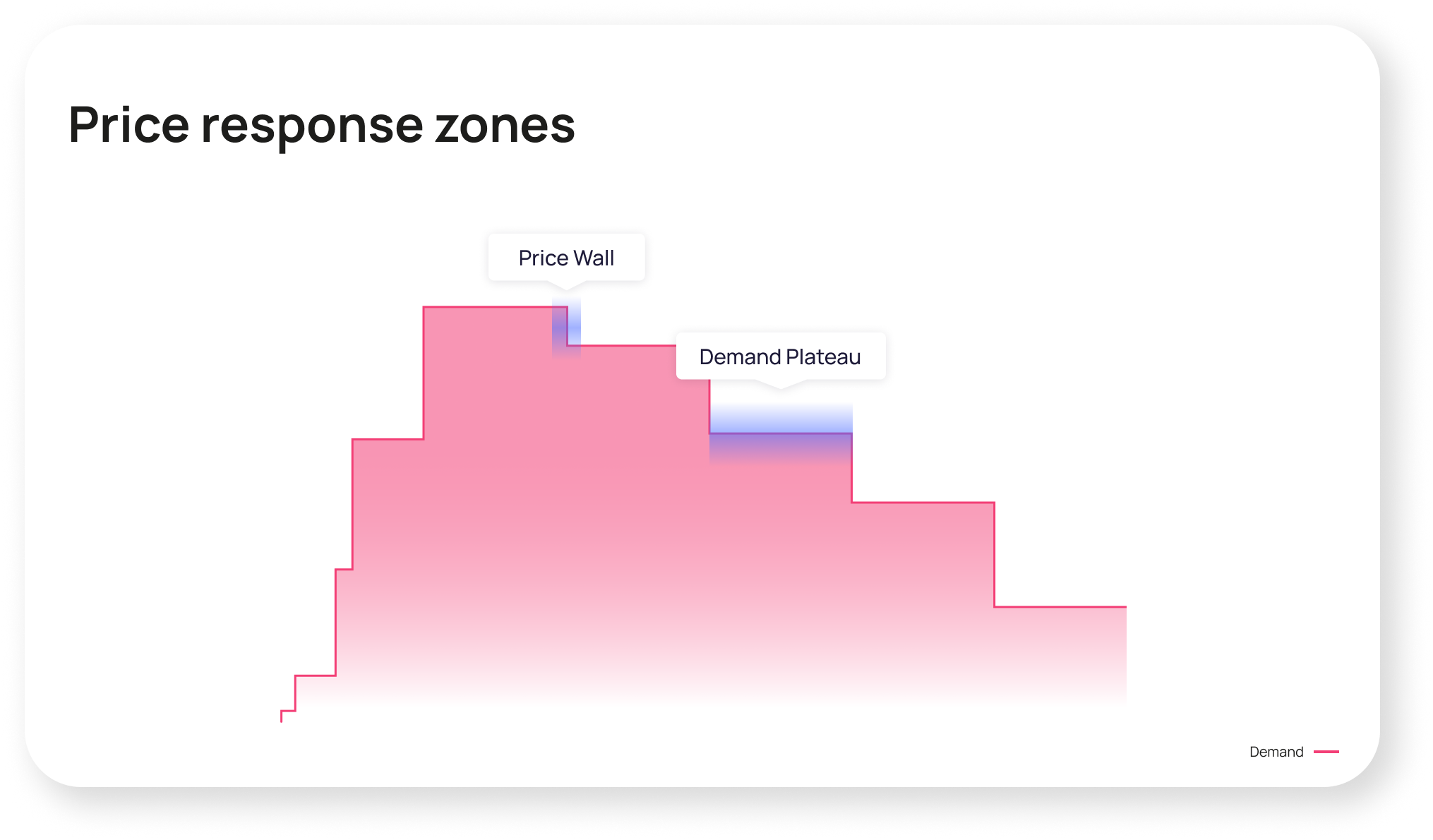

KVIs are better understood as thresholds than as labels.

The biggest shift in modern KVI thinking is not about tools or tactics. It is about perspective. Instead of treating KVI as a static label attached to a product, leading teams treat it as a question about demand behavior.

The traditional question is: “Which products are our KVIs?”

The more useful question is: “At which prices do specific products start to influence demand and perception disproportionately?”

That distinction matters because KVI behavior is rarely binary. Products do not suddenly become important the moment they are labeled as KVIs. Their influence emerges at certain price levels, driven by how willingness to pay changes. Below a threshold, demand accelerates and perception improves. Above another threshold, demand drops sharply or trust erodes.

Those thresholds are where KVI dynamics actually live.

Looking at KVIs this way changes how pricing decisions are made. Instead of defaulting to competitive matching or blanket discounts, teams can see where demand plateaus and where price walls appear. Some products tolerate higher prices without meaningful demand loss, even if they are frequently purchased. Others trigger strong reactions from relatively small price changes. Without visibility into that behavior, teams often over-invest in the wrong places.

A demand-first view also helps avoid false KVIs. Many products feel important but do not move demand, even though they are visible internally or discussed frequently, but their price has little impact on customer behaviour. Treating these as KVIs leads to unnecessary margin sacrifice. Conversely, some products quietly drive perception even though they are not internal favourites. These are easy to miss without looking at how demand actually responds across price points.

This approach becomes especially valuable during uncertainty. Cost increases, competitive moves, and market shocks all force pricing decisions to be made quickly. In those moments, historical sales data is least reliable. A demand-first KVI lens allows teams to evaluate trade-offs before acting, not after margin has already been lost.

The practical outcome is a more precise KVI strategy. You price aggressively where it truly changes demand and perception. You price confidently where demand is resilient. And you stop treating KVI pricing as a defensive exercise based on past behaviour, and start using it as a forward-looking decision framework grounded in how customers actually respond to price.

Conclusion

Key Value Items are a real and useful concept, but they are often applied too mechanically. Too many KVI strategies start with a list of products and end with competitive price matching, without ever questioning whether those items actually shape demand and perception in the way teams assume.

The core issue is not intent, it is visibility. When KVIs are identified mainly through historical sales, intuition, or static rules, teams see only what happened at the prices they chose. They miss how demand would have behaved at other price points, and they risk investing margin where it does not change customer behavior.

A more effective approach treats KVI as a demand question. Which products influence trust and price perception. At what prices does demand accelerate, flatten, or break. And how do those dynamics change by channel, moment, or market conditions. This applies just as much to companies with a handful of products as it does to retailers with thousands of SKUs. In fact, for small portfolios, getting this wrong is often more costly.

The takeaway is simple. KVI pricing works best when it is grounded in how customers actually respond to price, not in assumptions carried over from last year’s sales data. When teams understand where price truly matters, they can be aggressive with confidence and protective with intent.

If you want to revisit your KVI strategy, start by questioning your current assumptions.

Identify which products define your price image, explore how demand reacts across different price levels, and validate those insights before making pricing moves. That shift, from labeling products to understanding demand, is where KVI strategy becomes a real growth lever rather than a defensive tactic.