Smarter pricing, better promotions: why precision beats big discounts

How to design discounts that actually change buyer behavior.

Summarize article with AI

Many teams treat promotions as tactical levers. A discount here, a campaign there, aimed at nudging demand and sparking activity. The logic is intuitive. Drop the price and sales rise. Cut deeper and they rise more. This belief, that discounts automatically create demand, is precisely why most promotions fail.

In reality, a discount is not a marketing tactic.

It’s a pricing intervention.

You’re changing the product’s position on the demand curve, whether you realize it or not. And if that move doesn’t cross a real threshold where new customers say yes, the promotion doesn’t grow the pie, it just sells the same pie cheaper.

McKinsey data shows that 59 to 72 percent of trade promotions destroy value. Not because the idea of a promotion is flawed, but because most are built on assumptions, not demand signals. Most discounting is guesswork, not just in timing, but in targeting, depth, and mechanics. The result? Spikes that look good on a dashboard but disappear just as fast.

Priceagent identifies where those thresholds are. It shows whether a discount unlocks new buyers or simply donates margin.

Promotions are bets, not bargains.

A promotion is a price movement on your demand curve. You give up margin in exchange for access to buyers who are blocked at the current price. If you do not reach their threshold, nothing changes. If that demand does not exist, or if you do not move the price into a zone where customers respond, you do not create revenue. You reprice what you already had.

That’s why most promotions don’t grow the market. They simply compress it. They pull forward purchases that were going to happen anyway. Nielsen calls this out clearly: most retail promotions create zero net new demand. The spike is not new customers. It’s timing distortion.

Most promotions redistribute existing demand instead of unlocking new demand. The lift often reflects calendar timing, traffic intensity, or existing buyer momentum. Without visibility into where your current price sits on the curve, a discount has no causal interpretation. You cannot tell if it unlocked behavior or simply repriced existing buyers.

Most of your market isn’t even shopping.

Promotions assume price is the barrier. That everyone is waiting to buy if you go low enough. But most buyers are not held back by price. They are not in market at all.

Ehrenberg Bass shows that penetration, not deeper extraction from existing buyers, drives growth. Promotions rarely increase penetration. They simply remix when existing customers purchase, and at what price.

This pattern is consistent with the Dirichlet model of buying behaviour, which shows that categories are dominated by light buyers who purchase infrequently and whose probabilities of buying are remarkably stable over time.

Only the people already close to a purchase threshold respond to price drops. And if those customers would have bought anyway? You just gave them a discount for free.

Demand doesn’t rise smoothly. it moves in steps.

Promotions often follow linear logic. Ten percent off equals ten percent more demand. But human behavior does not move in straight lines.

Demand behaves in thresholds. There are periods of stability where price changes do nothing. Then there are psychological walls where even a small move triggers a shift in behavior. There are also floor price points that are so low they feel untrustworthy.

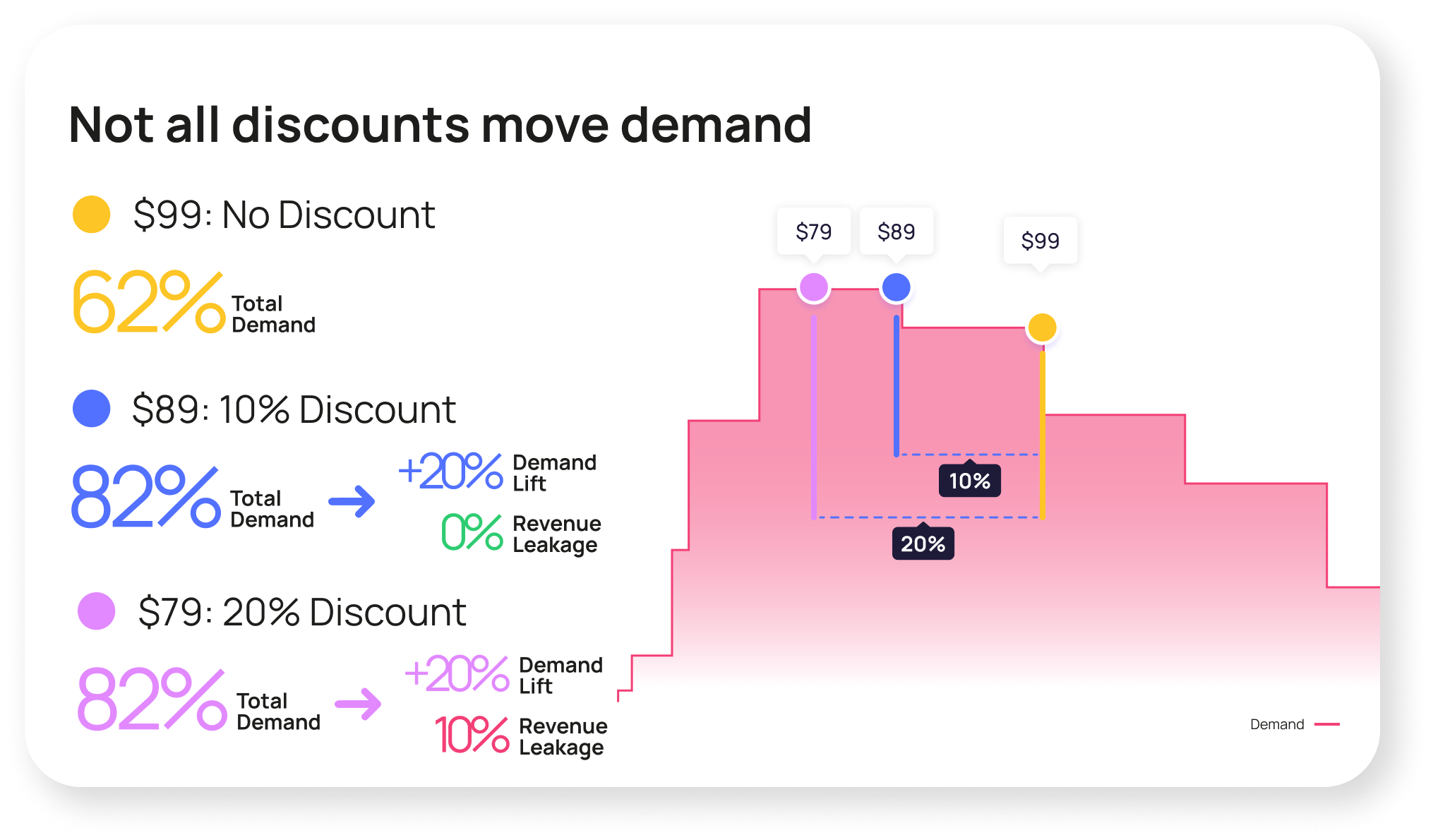

The simplest example illustrates the problem clearly.

A move from 99 to 89 is enough. It crosses the first wall and places you in a higher demand zone. Buyers who said no at 99 say yes at 89. Demand lifts. Revenue is protected. The discount is doing its job.

Move from 99 to 79 and you reach the same plateau. The extra ten percent does not create more demand. It only donates margin. The price crossed the relevant threshold, but too far. The discount is solving the same behavioral barrier with a deeper, more expensive move.

Promotions work when the price lands at the first threshold that changes behavior. Not short of it. Not far beyond it.

A plateau is not “how many people” you have. It is a stable demand range, the prices where willingness does not materially shift. A span like 10 to 19.99 can sit on the same demand level. Moving anywhere inside that span does not access new buyers. You only get a real change in demand when you cross into the next behavioral interval. If you discount into a lower plateau, you do not unlock a larger audience, you simply move to a weaker demand percentage and collect less value from each buyer.

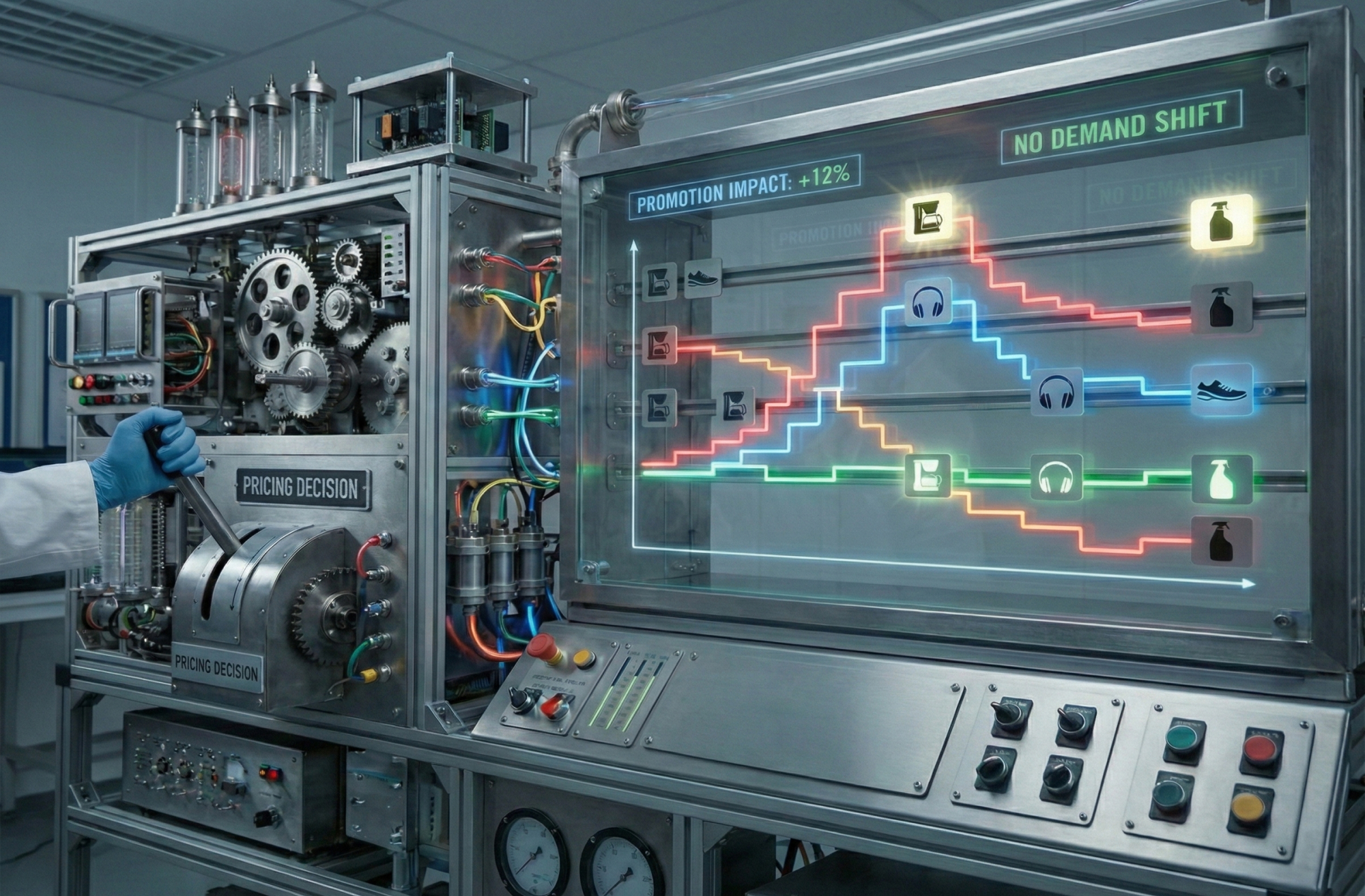

And those thresholds? they’re different for every segment.

A blanket discount moves every group the same amount, even though each group sits at a different distance from its own price wall. You end up giving margin to buyers who already would have converted, while failing to reach the cohorts that were actually blocked.

Promotions fail when you don’t know your baseline.

The root cause of most promo failure is this: teams don’t know where their current price sits on the demand curve before they start cutting. Without that baseline, a promotion is just a guess.

Baseline is your current position on the demand curve. It shows how buyers respond at the price you are charging, where the nearest demand walls sit, and which plateaus exist above or below you. Without that positional understanding, discounting cannot be interpreted. Every spike looks meaningful, even when it is just buyers moving within the same threshold.

There are only three places a discounted price can land.

- Discount in a plateau? You lose margin and nothing moves.

- Drop below credibility? You lose trust, and conversion falls.

- Move just past a price wall? You unlock real incremental demand.

Crossing a price wall only creates value if it leads into a plateau with higher demand. Crossing into a weaker plateau reduces demand. Staying in the same plateau changes nothing. Only a move into a stronger interval can unlock new buyers.

This is why measurement matters. Without incrementality, success is an illusion. Most campaign dashboards show volume spikes that feel exciting. But when compared to your full-price baseline, they underperform.

A promotion that sells more units but reduces total revenue is not a win. It’s margin donation. And if demand drops back to baseline the moment the discount ends, you didn’t create growth. You created a habit.

Incremental demand is the only metric that matters.

Incrementality only exists relative to your full price baseline. The baseline shows where your current price sits on the demand curve and which cohorts are blocked at that threshold. A promotion has potential when it crosses that wall. It is not deeper discounts that matter, but whether the move reaches the first behavioral point where new buyers begin to say yes.

If the same people buy, just sooner? Not growth.

If you move more units, but make less total revenue? Not growth.

If demand collapses after the promo ends? Not growth.

A successful promotion crosses a wall. It activates a cohort that was previously blocked. And it creates durable lift beyond the promo window.

This is the CFO lens: net new buyers, net new revenue, post-promo durability. If you can’t prove it, it didn’t happen.

And here’s where the logic is often misunderstood: promotions don’t expand the category. They only activate people who were already in motion. Ehrenberg-Bass research shows that category growth comes from penetration, not from extracting more from the same customers. Promotions remix timing and redistribute spend within the buyers you already have. Even when new customers appear, their behavior follows the same light-buyer pattern. They buy, they leave, and their probability of returning reverts to baseline, just as the Dirichlet patterns predict for repeat-purchase markets.

If a promotion doesn’t increase category entry, it isn’t growth. It’s just a temporary reduction in price paid by people who were already going to buy.

If you’re going to discount, do it with the curve in mind.

A good promotion is not about generosity. It’s about precision.

Step 1: map your demand position

You need to know where your current price sits on the full demand curve. Without that map, every discount is speculative.

Step 2: define your target cohort

Promotions should be surgical. Not broadcast. Know which segment you’re trying to move, and why.

Step 3: price to the threshold, not to aesthetics

Customers respond when price crosses a price wall. The smallest discount that gets you into the next stable zone of demand is the one that matters. Once you are there, you position the price as high as possible in that zone to maximize revenue, not to chase a round figure.

Step 4: measure incrementality, not spike size

Track net new buyers and net new revenue. That’s the signal. Volume alone is noise.

Step 5: learn what the result tells you

If discounting is the only way to move volume, you don’t have a pricing problem. You have a value problem.

Promotions are more than one format

Discounts are only one way to move price. Promotions also come as bundles, loyalty incentives, inventory clearance, rebates, trials, and value packaging. Each mechanic has its own goal. Some protect margin by reframing the offer. Some accelerate sell-through. Some reward existing buyers and increase frequency. Others reduce perceived risk to encourage first conversion. The tactics differ, but they all intervene in the same economic relationship between the buyer and the price.

A bundle does not feel like a discount, yet it changes how value is evaluated. A loyalty bonus does not move the sticker price, yet it reduces friction for known buyers. A clearance move is not a growth tactic, it is an operational decision to monetize stock. Each of these choices still interacts with demand thresholds. They influence who converts, when they convert, and at what effective price.

The mechanics matter, but they do not replace the fundamentals. Whether it is ten percent off, two-for-one, or a members-only incentive, the outcome depends on where the buyer sits relative to the relevant wall. A promotion that does not cross a behavioral threshold will not unlock new demand. It will only change how much value you capture from the buyers you already have.

Conclusion: discounting is not a reflex. it’s a strategic intervention.

Promotions are not bad. They are misused. They fail when teams do not know where their current price sits on the curve. Without that awareness, a discount cannot be interpreted. You cannot tell whether it unlocked new willingness or simply repriced existing demand.

A promotion only creates value when it crosses a price wall. Anything else is margin transfer. Priceagent makes those walls visible. You see where demand is stable, where it breaks, and where additional willingness sits beyond each threshold. With that visibility, a promotion is not a reflex. It is a deliberate move toward a cohort that was previously out of reach.